Recently, I read an interesting article in which a 20-year old Hunter S. Thompson gave life advice to his friend. In spite of his youth, the advice is pretty insightful.

The main question he tackled is, what should the goal of life be. How should one approach what one is supposed to do?

And indeed, that IS the question: whether to float with the tide, or to swim for a goal. It is a choice we must all make consciously or unconsciously at one time in our lives. So few people understand this! Think of any decision you’ve ever made which had a bearing on your future: I may be wrong, but I don’t see how it could have been anything but a choice however indirect — between the two things I’ve mentioned: the floating or the swimming.

One important point he made was that he could not set the goals for somebody else, because the other person’s capabilities and experiences were totally different.

That’s a reasonable argument. And if that argument does seem reasonable to you, then it takes just one little step further to argue that a young you cannot / should not set goals for an older you. Because you’re experiences and capabilities are changing throughout your life:

Every man is the sum total of his reactions to experience. As your experiences differ and multiply, you become a different man, and hence your perspective changes. This goes on and on. Every reaction is a learning process; every significant experience alters your perspective.

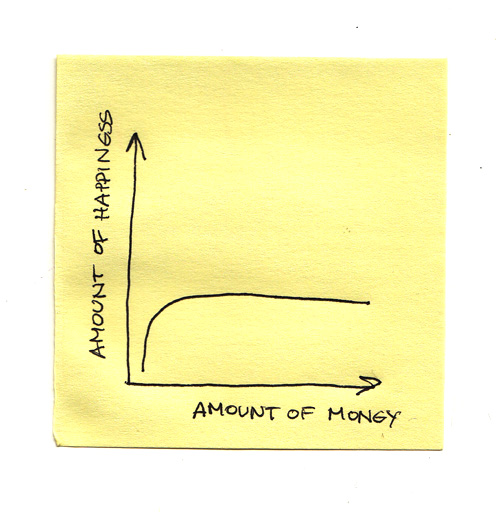

So it would seem foolish, would it not, to adjust our lives to the demands of a goal we see from a different angle every day? How could we ever hope to accomplish anything other than galloping neurosis?

Thompsons solution was to focus on abilities and desires instead of focusing on goals:

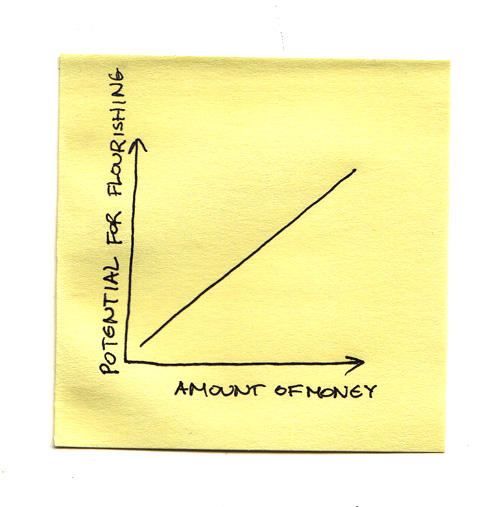

As I see it then, the formula runs something like this: a man must choose a path which will let his ABILITIES function at maximum efficiency toward the gratification of his DESIRES. In doing this, he is fulfilling a need (giving himself identity by functioning in a set pattern toward a set goal) he avoids frustrating his potential (choosing a path which puts no limit on his self-development), and he avoids the terror of seeing his goal wilt or lose its charm as he draws closer to it (rather than bending himself to meet the demands of that which he seeks, he has bent his goal to conform to his own abilities and desires).

In short, he has not dedicated his life to reaching a pre-defined goal, but he has rather chosen a way of life he KNOWS he will enjoy. The goal is absolutely secondary: it is the functioning toward the goal which is important. And it seems almost ridiculous to say that a man MUST function in a pattern of his own choosing; for to let another man define your own goals is to give up one of the most meaningful aspects of life — the definitive act of will which makes a man an individual.

If this seems all a little vague and hand-wavy to you, the same advice is given by Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert, but he says it in a more concrete and digestable format:

In my new book, How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big: Kind of the Story of My Life, I talk about using systems instead of goals. For example, losing ten pounds is a goal (that most people can’t maintain), whereas learning to eat right is a system that substitutes knowledge for willpower.

Here is another example of a system, as opposed to a goal:

When I first started blogging, my future wife often asked about what my goal was. The blogging seemed to double my workload while promising a 5% higher income that didn’t make any real difference in my life. It seemed a silly use of time

And here is the full story of how this “system” helped him achieve success that wasn’t really part of any goal, and was probably not something that he had even considered:

Writing is a skill that requires practice. So the first part of my system involves practicing on a regular basis. I didn’t know what I was practicing for, exactly, and that’s what makes it a system and not a goal. I was moving from a place with low odds (being an out-of-practice writer) to a place of good odds (a well-practiced writer with higher visibility).

The second part of my blogging system is a sort of R&D for writing. I write on a variety of topics and see which ones get the best response. I also write in different “voices”. I have my humorously self-deprecating voice, my angry voice, my thoughtful voice, my analytical voice, my half-crazy voice, my offensive voice, and so on. You readers do a good job of telling me what works and what doesn’t.

When the Wall Street Journal took notice of my blog posts, they asked me to write some guest features. Thanks to all of my writing practice here, and my knowledge of which topics got the best response, the guest articles were highly popular. Those articles weren’t big money-makers either, but it all fit within my system of public practice.

My writing for the Wall Street Journal, along with my public practice on this blog, attracted the attention of book publishers, and that attention turned into a book deal. And the book deal generated speaking requests that are embarrassingly lucrative. So the payday for blogging eventually arrived, but I didn’t know in advance what path it would take. My blogging has kicked up dozens of business opportunities over the past years, so it could have taken any direction.

Read both articles, you’ll like them: